Planning on taking a Chernobyl tour? Follow our journey through the snow....

This trip to a wintry Ukraine (there’s no need for a ‘the’ prefix anymore) is the deepest we’ve travelled into Eastern Europe, a part of the world which has witnessed such tumult and transformation in the decades following the denouement of the Cold War. As fans of all things Le Carré, the freezing temperatures feel somewhat appropriate for our journey east; shorts and sunshine aren’t things we’ve come to readily associate with post-Soviet hinterlands.

It’s hard to know exactly how to react to taking a tour to Chernobyl, situated just over 80 miles from Kiev, Ukraine’s capital. Should excitement enter the lexicon when heading to a place which, to so many, can and will only ever exist as shorthand for disaster?

‘Curious’ is probably the word which sums up our feelings best - curious to understand what exactly happened here, curious to witness the impact of nuclear fallout on the land and the environment, and curious to witness first-hand a place where humanity can no longer exist.

the radar

We were nearly half-way through our Chernobyl tour and the cold was beginning to take its toll on some of our group. Overnight, more thick snow had fallen, adding an extra centimetre or two to the white blanket which surrounded us. The air was crisp and fresh, but our breath formed spirals. It was minus eight degrees.

We decided to put on that extra layer.

Our bus had pulled up beside a dark green gate, branded with two over-sized silver stars, next to a defunct guard’s station. A short walk ahead of us, past walls of faded propaganda, broken windows and an abandoned truck lay, hidden in a forest, one of the Soviet Union’s greatest secrets.

"Are we supposed to be here?" I ask.

"We were never supposed to be here." Emily whispers back

Here, waiting for us in the snow-steeped forest was the Duga Radar, a gigantic snarling 14-ton structure of Soviet steel and industrial achievement, and an integral part of the Soviet Union's top-secret anti-missile defence programme. Responsible for the 'tuk-tuk-tuk' interference that plagued radio enthusiasts in Europe and the US, for most of its short life it never officially existed.

As with most that venture on a Chernobyl tour, we can be forgiven then for being unaware of the existence or indeed the importance of Duga until it was right there towering over us. This metallic colossus, which for so many years could not be found on maps, has to be witnessed in person to be truly appreciated and, even though its might, power and song are long forgotten, it intimidates.

This monument to a different age provided our first 'bloody hell' moment in Chernobyl; many more were still to come.

More importantly though, Duga offered the first hint at the hidden narratives and stories which can be found within the surprisingly verdant 30 kms Exclusion Zone. Although the opportunity to understand the disaster and its impact first-hand is what draws intrepid visitors here, it is Chernobyl's ability to unlock the psyche and intrigue of the Cold War which adds layers and texture to the experience. Indeed, one can only comprehend the Chernobyl disaster by setting it against the era where the world stood divided into two distinct and competing world views. Duga itself represents a vast, symbolic manifestation of the paranoia prevalent in the Party around attack and disaster from the outside by the 'other'; a mentality which perhaps contributed to a failure to appreciate what was happening only a few miles down the road at a nuclear facility which posed a much more immediate, home-grown threat to the very existence of this Empire in the East.

the plant

“The odds of a meltdown are one in 10,000 years. The plants have safe and reliable controls that are protected from any breakdown with three safety systems.”

Chernobyl today is an irradiated graveyard not only to forgotten villages and abandoned cities, but to Soviet ambition. Its role within the collapse of bloc, only five years later, cannot be underplayed.

In the midst of the arms race, proxy-wars and diplomatic stand-offs, Chernobyl's nuclear power plant formed a significant strategic part of the Soviets’ military-industrial strategy. Situated only 12 miles from Duga, it was an expensive flagship project, central to meeting the current and future energy requirements for the bloc (both civilian and military) and a sign that Soviet nuclear technology could compete with developments in the West.

However, within a system which stifled criticism and prioritised ends over means, shortcuts were inevitable in the attempt to maintain parity. The sort of shortcuts that led to the poor training and safety standards documented at Chernobyl, and created the conditions for that fateful Saturday morning where engineers undertook an error-strewn experiment.

The result was two explosions in reactor number 4 which would directly end the lives of 31 and ruin the lives of thousands more.

As we approached the epicentre in our tour bus, our guides advised all of us that our cameras had to remain firmly where they were; no photos were to be taken until advised. If you close your eyes now and picture what Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant looks like in 2017, I’m certain that hundreds of workers, new signs, cars, the odd dog or two and a lot of activity would not necessarily come to mind. And yet, here at the heart of one of only two events classified at level 7 on the International Nuclear Event Scale, it felt, well, normal.

In our minds, this was going to be a post-apocalyptic wasteland - barren and desolate. Such a facade of relative normality in this place of all places felt utterly surreal.

Shockingly, our guides explained, after the fire and nuclear fallout in reactor four, the vast site was not actually shut down and fenced, but actually remained a working power plant. Nuclear radiation or not, reactors one,two and three were still functional and Ukraine and Belarus (less than 12 miles away) still needed energy.

Workers, subject to time restrictions and higher than average pay given the risks, still shuffled in and out for years. And 3,000 continue to do so today.

Today, all the towers and reactors have been turned off. So why all the people and activity?

Well, it is all still tied to that pivotal event and the poor response of the Soviet authorities to it; the ‘sarcophagus’, the concrete encasing the government hastily put over reactor four to prevent more radiation spewing out, was at threat of crumbling and causing a whole new radiation scare at any given moment. The international community has funded the creation and installation of a recently installed new superstructure to protect the site for another century at least.

After all, a nuclear leak cannot be treated in geographical isolation; the wind knows no borders.

With my Le Carré hat still firmly on, we have to add that this is the official reason given for the fact we can’t take photos...and we still have our suspicions about whether something else is happening here. Let’s not forget that this is a site which still holds the raw materials to create something altogether more destructive when put in the wrong hands.

“For the attention of the residents of Pripyat! The City Council informs you that due to the accident at Chernobyl Power Station in the city of Pripyat the radioactive conditions in the vicinity are deteriorating. The Communist Party, its officials and the armed forces are taking necessary steps to combat this. Nevertheless, with the view to keep people as safe and healthy as possible, the children being top priority, we need to temporarily evacuate the citizens in the nearest towns of Kiev Oblast. For these reasons, starting from April 27, 1986 2 p.m. each apartment block will be able to have a bus at its disposal, supervised by the police and the city officials. It is highly advisable to take your documents, some vital personal belongings and a certain amount of food, just in case, with you. The senior executives of public and industrial facilities of the city has decided on the list of employees needed to stay in Pripyat to maintain these facilities in a good working order. All the houses will be guarded by the police during the evacuation period. Tovarishchs, (Comrade) leaving your residences temporarily please make sure you have turned off the lights, electrical equipment and water off and shut the windows. Please keep calm and orderly in the process of this short-term evacuation.”

the town

It is in Pripyat where the human impact of the Chernobyl Disaster feels most prevalent. Only created in 1970 in order to provide accommodation and a ready-made community for workers of the nuclear plant and their families, this was a new settlement to herald the progress and advancement of the era.

Today it can only be described as a ghost town, left to decay and crumble into dust.

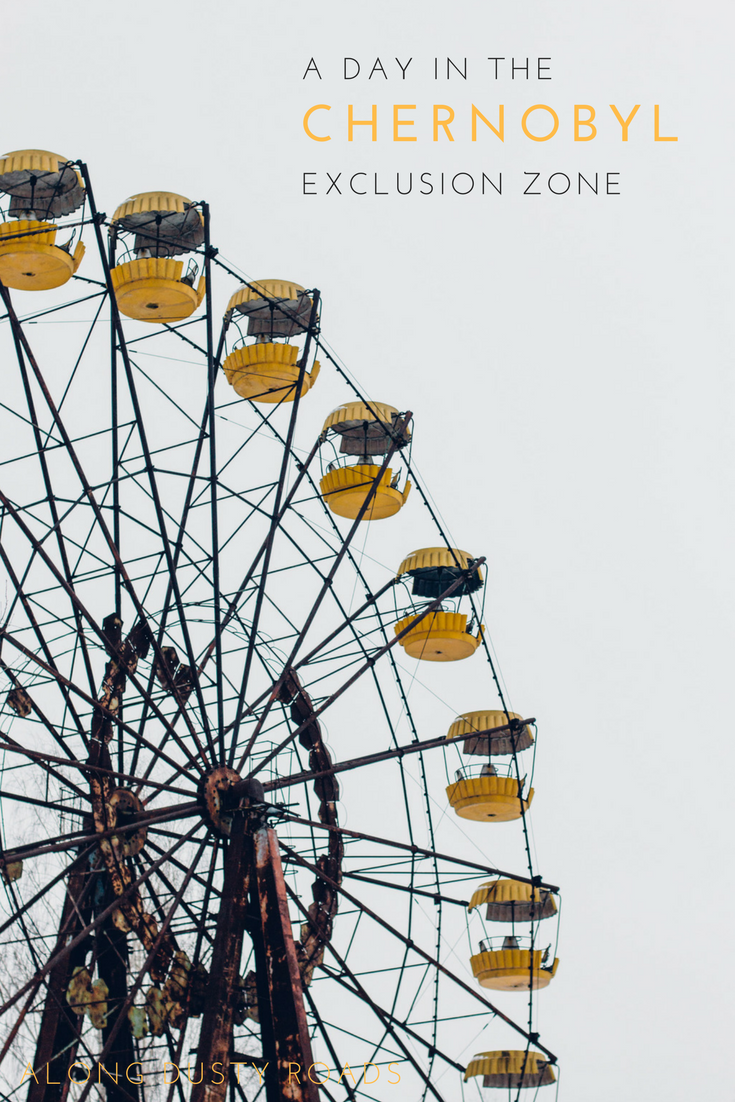

The aisles in the Pripyat's supermarket, though long emptied of their goods, still have their blue and white banners from 1986 to tell shoppers where to find the vegetables. Opposite, the grand hotel, with its imposing red sign, dominates the town square and was clearly once a class apart and the choice for visiting dignitaries or influential party officials. Old propaganda posters and signs, including a Lenin painting, dot the streets and walls. A short walk away, a sunshine yellow set of dodgems and a picture-perfect ferris wheel can be found in the park, dusted in virginal snow. One can only imagine how excited the children of this town of 50,000 must have felt to finally get the chance to ride it with friends - it was due to be opened the weekend after the explosion.

It remains, still awaiting its first customer and offering little more than a monument to the childhoods which Pripyat would never have the chance to witness and the memories it never was able to create.

Chernobyl was, fundamentally, totally and utterly avoidable. The debate over nuclear energy and humanity is for another day but we were shocked to understand that the nuclear explosion here was not as dramatic in its provenance as we had previously assumed. The disaster which released at least 100 times more radiation than the atom bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, was due to poor training, poor checks and safety protocols, woeful response times and a system of government which preferred to hide and delay, rather than notify.

Sometimes for us millennials growing up in a democracy, it’s difficult to understand the pace of things in the pre-internet age, let alone in the bureaucratic and secretive Communist state. In 1982, there had been a partial meltdown at the site, the full extent of which was not made public until 1985; in that same year the Energy Minister outlined that ‘adverse’ effects of the industry were not to be published by newspapers, radio or television.

No debate, no questioning, no option.

Such secrecy and obfuscation was all too evident on the 26th of April, 1986. In Pripyat, warnings were blurted out via speakers on lampposts and over the radio over 24 hours after the accident, informing the residents to gather their belongings and arrange to leave in the next two hours. The signs of the rush are still evident to those visiting today - scattered items poking out from under the snow remain and, if a ghost town isn’t eerie enough, a relatively modern ghost town created within the space of 48 hours and almost entirely untouched since then, certainly has an altogether stranger impact.

As the remainder of our group continue to take photos, we follow our guide - dressed in a black bobble-hat and with a cigarette perpetually dangling out the side of his mouth - back through the snow. Ahead of us, in that unmistakable brutalist functional design, are two grey apartment blocks; identical except for one crucial detail. Both have a metallic structure at the top - one red and gold, the other blue and gold - with a hammer and sickle forming the centrepiece. We ask our guide what they are and what they mean. “Coats of arms for the Soviet Union" he tells us. "Those are probably the last ones in the whole of Ukraine”.

Toxic symbols, in more ways than one. Visiting the Exclusion Zone, one gets the sense that, quite aside from the radiation levels, this place is home to more than a few relics of an age which Ukrainians would be happier to leave here, untouched, rusting and rotting.

the children

Previously, when the ‘dark tourism’ of Chernobyl was in its infancy, it was possible to enter into the abandoned buildings, seemingly at will. To gaze upon homes left in a hurry and precious items left behind by generations - pianos, photos, signs of family life. However, due to growing health and safety concerns at the state of buildings which have been left with the elements as their only occupants, there has been a crackdown on this.

One of the few remaining sites which visitors can enter on a tour is the abandoned nursery in the middle of the countryside; stepping through its doors is an experience not for the faint of heart. Although we're pretty certain that elements of it have been stage-managed to create a setting which gives you not just the heebies, but also the jeebies, it is a sobering, surreal experience. Toys and dolls lay scattered amongst books and pencils, rusting iron-frame cots stand in rows and each room is an experience in finding a more macabre scene straight out of a horror movie.

This is one of the few parts of Chernobyl which ticks that post-apocalyptic vision we had in our heads.

Outside the nursery, our guide took our yellow dosimeter, which is a strikingly similar share of sunshine yellow as the Pripyat ferris wheel and is a prop for tourists rather than a safety requirement. The click and beeps rapidly increased as he held it to a hole in the ground - a stark reminder that this is not a living museum or urban playground for tourists to do as they please. Vast swathes of the land here are still completely off-limits and will likely remain so for decades.

Before re-boarding our bus, we take the opportunity to look back at the nursery, and our eye is drawn to the statue of a soldier who stands mournfully in the snow outside it.

Predating a time when anyone in the Western Europe would have known of the name Chernobyl, it reminds us that although we’re almost exclusively viewing this region through the prism of one tragedy and its Cold War context. There was a world here with stories to tell before the Duga, before the reactor and before those two explosions.

Stalin's misguided and aggressively implemented policy of collectivisation in the early 30s saw over 5 million Ukrainians die in the Holodomor famine. A decade later the Nazi occupation of World War Two claimed over 3 million lives.

Ukraine is a country which has long known tragedy in all of its most brutal forms.

the impact

“The nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl 20 years ago this month, even more than my launch of perestroika, was perhaps the real cause of the collapse of the Soviet Union five years later. Indeed, the Chernobyl catastrophe was an historic turning point: there was the era before the disaster, and there is the very different era that has followed.”

Our visit to Chernobyl dispelled a number of assumptions we previously held about occurred here. Primarily, the death toll from the explosion and the efforts to contain it, though tragic, was relatively small at 31. The dissonance between the number of deaths we in the old ‘west’ continue to assume to have occurred in 1986 is largely down to the secrecy, confusion and political intrigue of the time leading to inflation and wild over-estimations in our own media - it was suspected and continually reported that thousands had perished in the immediate aftermath. The impact of such dramatic exposure to radiation on life-expectancy is however something which is still oft-debated and controversial; the estimates on deaths which will occur directly due to the Chernobyl exposure effect range wildly from around 10,000 to 200,000.

What is undoubted however is the direct emotional and economical impact on Ukrainians and Belarusians from this event runs deep - communities were broken up and moved from their villages and towns, farms rendered untouchable, ways of life lost. Some hardy stubborn souls did return to the only place they had called home - most famously the Babushkas - and refused to leave despite the risks in the Exclusion Zone, but they were the exception and very few remain.

For Ukrainians, aside from the varied emotional, environmental and economic costs of Chernobyl, it has meant that many outsiders only ever know their country for one terrible event.

And that in and of itself is one further tragedy.

So, why should you visit Chernobyl? What does visiting this isolated, silent outpost offer beyond the opportunity to shock a few people by saying you've been there?

For us, you should visit, because there is nowhere else on earth quite like it. The disaster not only had a physical and psychological impact on humanity which pervades to the present day, but its geo-political significance in the Cold War era cannot be underestimated. This explosion, caused through a system of control, censorship and clumsiness, crippled the military and energy strategy of the Soviets but, further, almost bankrupted it. Already struggling to keep pace with Reagan’s zealous defence spending, the Communist state could not simply absorb the $18 billion USD spend required to contain the aftermath of the nuclear fallout.

To visit here, is to not only understand the events and impact of one of the 20th century’s most notorious incidents, but to gain a unique perspective into a bygone era, when East and West stood divided, with two competing visions for how a society should be formed.

Although, as Gorbachev believes, the events of a single day here in April 1986 were pivotal in signalling the death-knell for the Soviet Union and triggering a financial collapse which precipitated its downfall five years later, it is ironic that it is in this small, abandoned pocket of northern Ukraine, where the Soviet Union itself never actually died. There was no perestroika, no glasnost, no tearing down of Party-approved relics and symbols, no declaration of independence.

Indeed, discovering Chernobyl in the snow reveals to us that we are in one of the few places in the world where the Soviet Union remains; and after thirty-one harsh Ukrainian winters, it can still be discovered here in the forest, frozen in time.

Booking Chernobyl Tours

It is only possible to visit Chernobyl with an approved tour company. We were guests of Planet Chernobyl, a new French tour operator who organise weekend packages with direct flights from London, Paris, Brussels, Frankfurt and Geneva. Packages include flights to Kiev, transfers to and from the airport, and two to three nights accommodation in Kiev, as well as your guided Chernobyl Tour experience.

For more information, visit their website here.

All views, photos and spelling mistakes are our own.